News Citation : 2026 LN (SC) 62

January 16, 2026 : The Supreme Court has issued a sweeping set of directions to address the rising number of student suicides across higher educational institutions, invoking its extraordinary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution. The Court described the crisis as an “iceberg of student distress,” driven by structural inequalities, academic pressure, lack of mental health support, and financial stress, and called for urgent, enforceable systemic reforms.

A Bench of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan passed the directions while hearing a criminal appeal in Amit Kumar & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. The Court had earlier constituted a National Task Force (NTF) to examine the root causes of student distress in higher educational institutions and to suggest comprehensive measures to ensure student mental well-being.

At the outset, the Bench expressed deep concern over the continuing spate of student suicides. It noted that even during the pendency of the case, several new incidents had been reported from campuses across the country, underscoring the gravity and immediacy of the problem.

Relying on National Crime Records Bureau data, the Court recorded that 13,000 student suicides were reported in 2022 alone. Analysing Sample Registration System data, it observed that suicides are either the second leading cause of death among men aged 15–29 or the leading cause among women in the same age group, far outpacing medical causes. The suicide rate in India for this age group, the Court noted, is significantly higher than global averages.

The NTF’s interim report, placed before the Court, was based on extensive research. This included nationwide surveys of students, faculty, parents, mental health professionals, and institutions, as well as 30 on-site consultations across 19 institutions in different States and disciplines. The Court said the findings revealed that student suicides are only the visible tip of a much larger problem of unaddressed distress within higher education.

The Bench pointed to the rapid “massification” and “privatisation” of higher education, which has led to unprecedented enrolment without a corresponding strengthening of institutional support systems. While affirmative action policies have improved access, the Court held that they cannot stop at admissions alone and must extend to sustained academic, social, and psychological support.

In a strong indictment of institutional failures, the Court found that Equal Opportunity Cells and Internal Complaints Committees often exist only on paper or function in a tokenistic manner. Even where they are formally constituted, the Court said, they frequently lack independence and may end up protecting perpetrators rather than students. The persistence of ragging, often trivialised as a “bonding exercise,” was also flagged as a continuing threat to student safety and mental health.

On campus mental health services, the Court noted severe gaps. Around 65 percent of surveyed institutions did not provide access to any mental health service providers, and nearly three-quarters lacked full-time professionals. Financial stress emerged as another major trigger, with widespread delays in scholarship disbursals pushing vulnerable students into distress.

Noting that several policies and regulations already exist, the Court identified a serious implementation deficit. Measures relating to ragging, equity, grievance redressal, and mental health, it said, are scattered across multiple documents, allowing accountability to “slip through the cracks.”

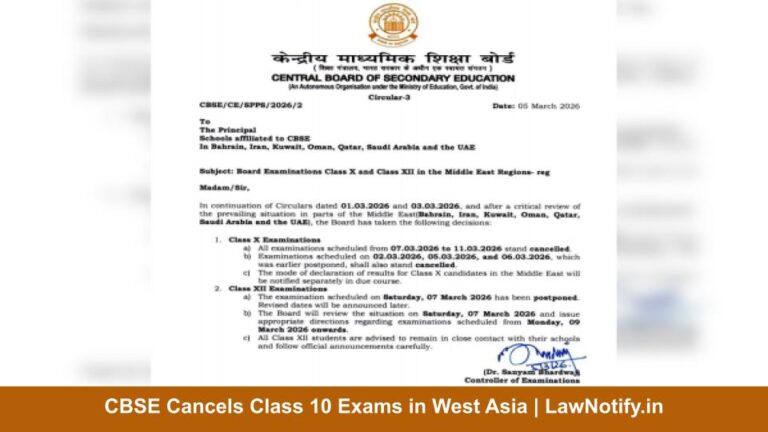

Exercising its powers under Article 142, the Court issued nine binding directions. These include centralised maintenance of suicide data for the 15–29 age group, clearer categorisation of student suicides by the NCRB, mandatory reporting of all student suicides or unnatural deaths by institutions to the police, and annual reporting of such cases to regulatory bodies like the UGC, AICTE, NMC, DCI, and BCI.

The Court also mandated round-the-clock access to medical help for residential institutions, time-bound filling of vacant faculty and administrative posts, and clearance of all pending scholarship dues within four months. It categorically directed that no student should be barred from classes, examinations, hostels, or denied certificates due to delays in scholarship disbursement.

All higher educational institutions were put on strict notice to comply fully with binding regulations on ragging, equity promotion, sexual harassment, and student grievances, failing which serious consequences may follow.

Going further, the Court directed the NTF to prepare model Standard Operating Procedures for periodic “well-being audits,” faculty sensitisation and training, and campus mental health services. These SOPs are to include clear evaluation parameters, compliance mechanisms, scoring systems, and even integration with NAAC grading. The NTF was also asked to develop a consolidated “Universal Design Framework” or “Suicide Prevention and Postvention Protocol” to bring all measures under a single, coherent guiding document.

Expressing disappointment at the general apathy shown by many institutions, the Court remarked that the lack of even basic cooperation with the NTF reflected deep-rooted barriers to reform. It directed the Union and State Governments to immediately circulate its directions to all higher educational institutions and ensure strict compliance.

The Bench concluded by placing on record its appreciation for the NTF, acknowledging the commitment and rigour with which it has approached the sensitive and complex issue of student suicides in higher education.