New Delhi : The Supreme Court of India has set aside the removal of a judicial officer with nearly three decades of unblemished service, holding that disciplinary action cannot be based solely on allegedly incorrect bail orders unless there is clear evidence of corruption, extraneous considerations, or misconduct.

A Bench of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and K.V. Viswanathan allowed the appeal filed by Nirbhay Singh Suliya, a former Additional District and Sessions Judge from Madhya Pradesh, who was dismissed from service in 2014. The Court found that his removal rested entirely on four bail orders passed under the Madhya Pradesh Excise Act, 1915, without any material to suggest dishonesty or corrupt motive.

The controversy began with a complaint made in 2011 by Jaipal Mehta, alleging that Suliya accepted bribes through his stenographer for granting bail in excise cases involving large quantities of liquor. The Supreme Court noted that the complaint was vague, did not identify specific bail orders, and largely targeted the stenographer rather than the judge. Importantly, neither the complainant nor the stenographer was examined during the departmental inquiry.

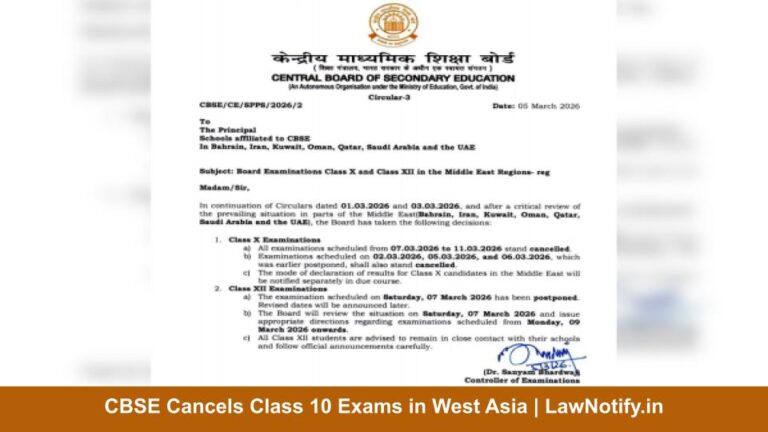

Departmental proceedings were initiated on two charges. While one charge relating to a rape case bail was ultimately found not proved, the inquiry officer held that Suliya had violated Section 59-A of the Excise Act in four bail orders by not expressly referring to its “twin conditions,” even though he had rejected bail in several other similar cases. This was treated as evidence of a “double standard” and led to his dismissal. His departmental appeal failed, and the Madhya Pradesh High Court dismissed his writ petition in 2024.

The Supreme Court found the inquiry deeply flawed. A key defence witness, Public Prosecutor K.P. Tripathi, who had appeared in all 18 bail matters examined in the case, testified that the bail orders were proper and that he saw no double standard in the judge’s approach. Another departmental witness, an executive clerk, also supported the defence and denied any knowledge of corrupt practices. Despite this, the inquiry officer concluded that Suliya had acted with mala fide intent.

Writing the lead judgment, Justice Viswanathan underscored that a wrong or imperfect judicial order cannot automatically be equated with misconduct. Relying on precedents including Union of India v. K.K. Dhawan and R.R. Parekh v. High Court of Gujarat, the Court reiterated that disciplinary action is justified only where conduct reflects lack of integrity, recklessness, undue favour, or corrupt motive. A mere error of judgment or technical lapse does not meet that threshold.

The Bench also referred to Sadhna Chaudhary v. State of Uttar Pradesh to caution against targeting judges who adopt a liberal approach to bail, observing that such decisions, by themselves, cannot justify doubts about integrity. The Court warned that disgruntled litigants and unscrupulous elements sometimes misuse complaints to intimidate trial judges, and that High Courts must act as a shield for upright officers.

Rejecting the High Court’s refusal to interfere, the Supreme Court held that judicial review is warranted where findings are perverse or unsupported by evidence, as laid down in Yoginath D. Bagde v. State of Maharashtra. It concluded that no reasonable person could have reached the inquiry officer’s findings on the material available.

Setting aside all impugned orders, the Court declared that Suliya would be deemed to have continued in service until superannuation. It directed payment of full back wages and consequential benefits within eight weeks, along with 6 percent interest. In an administrative direction, the judgment was ordered to be circulated to the Registrars General of all High Courts to ensure that these principles guide future disciplinary actions.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Pardiwala highlighted the chilling effect such proceedings have on the trial judiciary, noting that fear of disciplinary action often discourages judges from granting bail, pushing routine matters unnecessarily to higher courts. Invoking the maxim Nemo Repente Fuit Turpissimus, he cautioned against branding officers with long and clean service records as having doubtful integrity without solid evidence.

The ruling in Nirbhay Singh Suliya v. State of Madhya Pradesh and Another marks a strong reaffirmation that judicial independence cannot be compromised by treating alleged errors as misconduct.